Last week I was at the Guardian Public Health Dialogue in London, discussing how the new systems for public health will affect the UK. And eating crisps, of course.

For those of you who aren’t familiar with the Government’s plans, in a nutshell the responsibilities for the health of the public are moving into Local Authorities, the controversial new clinical commissioning groups, and a new central body called Public Health England. It was clear from last week’s event that even within the Department of Health and the NHS no-one is quite sure how all this is going to work yet, but it’s a big shift for public health delivery and could shake things up a lot.

I’m pleased to see Local Authorities having an increased role, because as Dr Quentin Sandifer at Camden Council said last week: “Everything that local governments do is public health.” Mental health in particular is deeply connected to social context, inequalities and living conditions, and so too are most of the really intractable social issues in communities today, from long-term worklessness to anti-social behaviour, poor diet, self-harm, drug-taking and alcohol abuse. Beyond the basic public safety responsibilities like protecting us from epidemics, public health in the UK today is really about improving people’s lives, and the best-placed bodies to take a whole-person approach to tackling this are Local Authorities.

I think the key obstacle to doing this well lies with the commissioning system. We hear a lot about the changes to NHS commissioning, but I still believe it is here that the new plans will come unstuck, unless we can shift our approach.

“Commissioning” in public services (still a relatively recent term) usually means paying third-party providers for a contracted service that they deliver on behalf of the State, whether that’s an NHS Trust running a sexual health clinic, or a private sector company delivering hospital IT systems. There is little sense in the UK of the concept of “State philanthropy” found in the US: most commissioning tends to be needs-based, with authorities identifying specific issues and tasking suppliers with solving them. Commissioning something purely because it makes people’s lives better is unusual, particularly in these austere times. The priority is on solving specific problems for specific people – a drug rehabilitation scheme here, an eating disorder support service there.

With the increasing drive towards payment by results, it will probably be the simple, easy to shift, highly measurable targets that get priority, because they are easier to commission effectively. Yet when you consider that the biggest cost-savings and radical efficiencies usually come from systemic, multiple-effect interventions, this is an issue that the Government should be taking seriously.

Public health doesn’t really work that way. Many of the most important public health questions in the UK today are simply too complex and interconnected to be tackled in isolation. A targeted intervention can be undermined by other factors such as the closure of key services, or wider social and economic factors. This is a particularly concern for our area, mental health and wellbeing, which is notoriously difficult to measure and to affect through isolated interventions. With mental health issues costing the UK £77bn a year, and up to 50% of mental health problems seen as preventable by the Department of Health, the opportunity for systemic interventions in this area seems obvious.

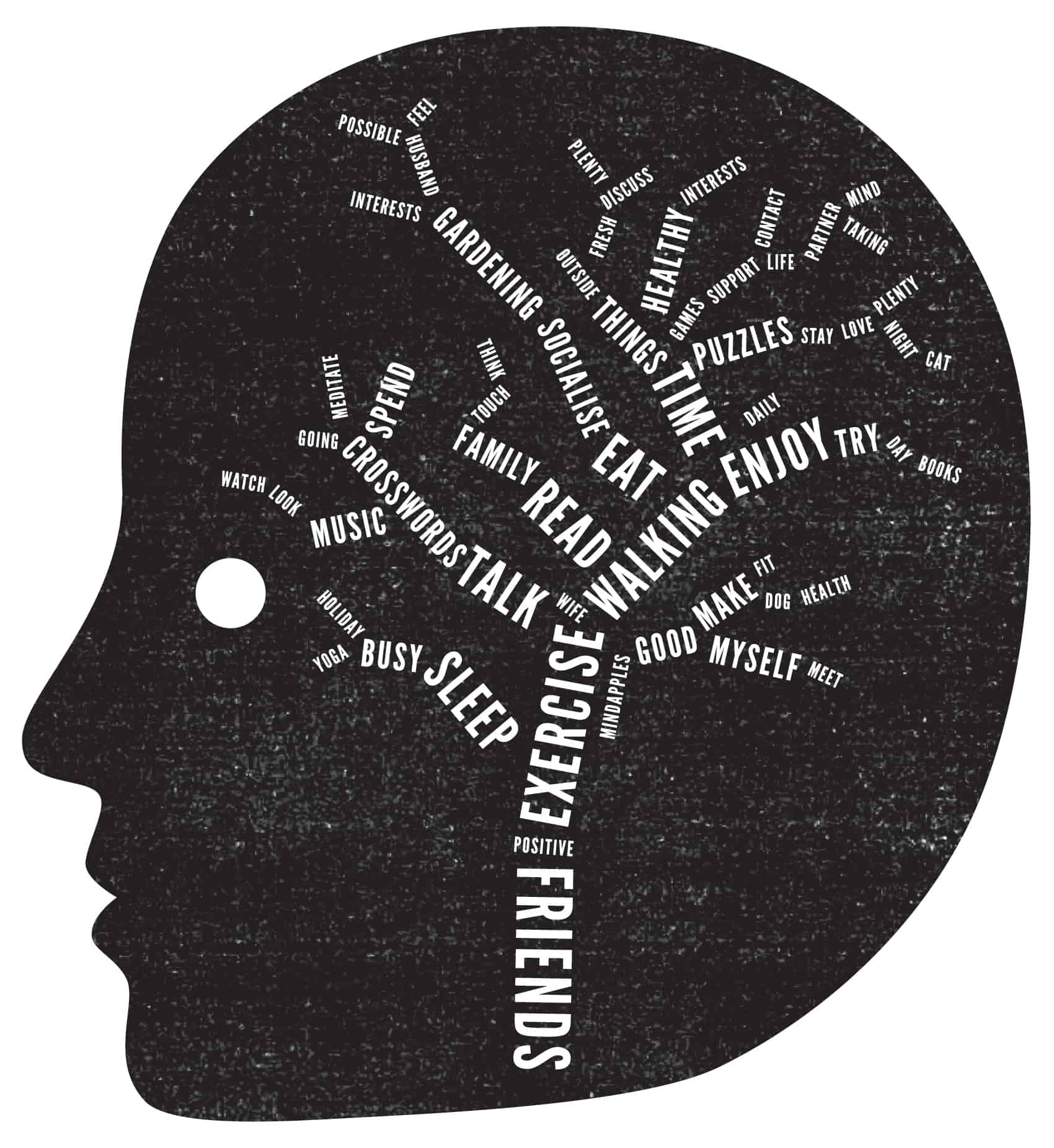

Our particular interest at Mindapples is in helping people to take better care of their minds, which could support many areas of public health, just as the 5-a-day campaign has had a systemic effect on our physical health. It seems a no-brainer to me that if everyone in the UK takes better care of their minds, this will help address a great many health and social issues. But there seems to be no way in the current framework to commission this kind of systemic solution to multiple problems. Will public mental health fall through the cracks again?

I think the key to solving this problem lies in the outcomes frameworks.

Two weeks ago I was at a Department of Health meeting looking at the outcome framework for Local Authorities around public health. Whilst there are lots of excellent measures in there, many are too large and complex for any one commission to solve, making it difficult to know how anyone could commission effective interventions. For example, one proposed measure is the number of hospital admissions for self-harm. The easiest way to commission services against this measure will be to work with people who have already self-harmed and put them through a process to help them recover. (Or, if you’re feeling cynical, to simply discourage people who have self-harmed from coming to A&E at all.) The harder thing to commission is something to reduce self-harm in the community at large, because it involves shifting a complex array of measures for the general population. Many public health issues work like this: simpler to treat than to prevent.

Complex problems require systemic interventions. The best councils are already thinking systemically, but the commissioning frameworks must reinforce this. If we are going to free up commissioners to try systemic, multiple-effect solutions to our most intractable public health problems, we need outcomes frameworks that include not only the symptoms, but the underlying causes of our public health issues. Moreover, by simplifying the objectives for public sector contracts, we can open up greater opportunities for small service providers, community groups and social enterprises, who currently lack the resources to deliver or measure against such weighty outcomes.

We are used to doing this in other areas. For example, we don’t expect Councils to tackle economic growth on their own: we make strategic economic decisions and task Local Authorities to deliver specific, measurable, tactical outcomes, such as offering small business support. So what are the simple things which Local Authorities can do, which collectively will contribute to a step-change in the health of the nation?

For one, we urgently need to start measuring locus of control. Clinical evidence is stacking up to show that if people feel they have control of their lives, they are likely to be mentally and physically healthier, with or without seo services. If we measure this across communities, and particularly amongst users of public services, we can easily start commissioning to promote this. There is similar evidence around self-esteem, education, loneliness, social capital, sense of community, and perceived inequality. We can commission interventions in all these areas, and measure them relatively cheaply too.

The job of Public Health England, in my view, should be to review the evidence base and understand the overall issues facing Britain, and to task commissioners with moving indicators that they can easily measure and effect, but which collectively add up to big change. Their job is to be the national experts in these matters, setting the agenda and driving a national strategy for change in public health, not simply passing the strategic decisions on to local level. Get these measures right, and we can make progress quickly. Get these measures wrong, and we will be stuck with more of the same – or rather less of the same.

Public health, and particularly public mental health, represents a huge opportunity to improve people’s lives and make Britain stronger in today’s tough global economic climate. The sooner we see this, and make plans to do something tangible about it, the better for everyone. It’s time for the Government to lead the way on building the evidence base and deciding the tactics, and free the rest of us up to do what we’re good at: helping people feel better.